Japanese Belief Systems

If you are planning on visiting Japan and perhaps experiencing some of the many beautiful Shrines and Temples, then you might be interested in learning about the two main Japanese belief systems beforehand.

As stated in the title, this is only a basic guide intended for visitors to Japan.

Japan has two main belief systems, Japanese Buddhism and the native Shintoism. Although there are some distinct differences between the two, they are not conflicting, and often compliment each other.

Many Japanese people will follow Japanese Buddhism and Shintoism together, as they are both an integral part of traditional Japanese cultural beliefs and practises.

This complimentary existence of the two systems can be seen by the close proximity and relationships between many Buddhist Temples and Shinto Shrines.

In fact, until the Meiji Era (an era which succeeded the Tokugawa Shogunate, restoring Imperial rule to Japan) many Buddhist Temples and Shinto Shrines were combined and operated as a single space serving as both the Temple and Shrine.

The Meiji government ruled that Temples and Shrines should operate separately. However, at some sites the close proximity of one to the other can still be seen today, and suggests a history of cooperation and collaboration between the two.

A Brief History

Shintoism

Shintoism is Japan’s indigenous belief system, translating as “the way of the gods”, and predates recorded history. There is no known date which precisely marks the founding of Shintoism.

Shintoism is polytheistic, involving the veneration of many deities known as Kami. It is often said that there are eight million Kami, a number which connotes an infinite number.

The word Kami does not directly translate into English but may be rendered as gods or spirits. In Japanese it is often applied to the power of phenomena that inspire a sense of wonder and awe in the beholder.

Kami are seen to inhabit both the living and the dead, organic and inorganic matter, and natural disasters like earthquakes, droughts, and plagues; their presence is seen in natural forces such as the wind, rain, fire, and sunshine.

Kami are deemed capable of both benevolent and destructive deeds. If warnings about good conduct are ignored, the Kami can mete out punishment, often illness or sudden death, called shinbatsu.

Kami are not considered metaphysically different from humanity, with it being possible for humans to become Kami.

Ancestors and other dead humans are sometimes venerated as Kami, being regarded as protectors. For example, Emperor Ōjin was posthumously enshrined as the Kami Hachiman, believed to be a protector of Japan and a Kami of war.

It is quite typical to visit the local shrine when moving to a new area, or facing a change in ones life to pay respects to and ask for protection from the Kami of the local area.

While there is a belief in the human spirit or soul, modern Shinto places greater emphasis on this life than on any afterlife. Buddhism is often the chosen belief system for dealing with the afterlife in Japan.

Shintoism focuses on ritual behaviour rather than doctrine. It encourages the practitioner to respect their own spirit and their surroundings.

Japanese Buddhism

Originating in India, Buddhism arrived in Japan around the 6th century, after first travelling through China and Korea.

However, today most of the Japanese Buddhists belong to new schools of Buddhism which were established in the Kamakura period (1185-1333).

There are many schools/sects of Buddhism in Japan, the oldest today being the Six Nara Schools which arrived in Japan from China and Korea in the 6th century.

Between the years of 781 and 806, the then Emperor Kanmu became disenchanted with the increasing power and political influence of the Six Nara Schools, overwhelming the capital city of Nara.

He relocated the capital to Heian-kyō (modern day Kyoto) and directly encouraged the creation of the Tendai school, founded by Saichō, and the Shingon school, founded by Kūkai.

This period saw the development of Shugendō, founded by En no Gyōja as an eclectic tradition which brought together Buddhist and ancient Shinto elements.

During the Kamakura period (1185 – 1333), many new Buddhist schools were founded, classified by scholars as “New Buddhism” (Shin Bukkyō), as opposed to “Old Buddhism” (Kyū Bukkyō). It is these “New Buddhism” schools which today have the most followers in Japan.

After thriving during the Edo Period (1603 – 1868), Japanese Buddhism would experience some adversity in the Meiji Era (1868 – 1912).

The Meiji Restoration, at the time referred to as the Honourable Restoration, was a political event which restored imperial rule to Japan in 1868, under Emperor Meiji.

The imperial Meiji Government adopted a strong anti-Buddhist attitude. A new form of pristine Shinto, stripped of all Buddhist influences, was promoted as the state religion and an official state policy known as shinbutsu bunri (separating Buddhism from Shinto) began with the Kami and Buddhas Separation Order (shinbutsu hanzenrei) of 1868.

The ideologues of this new Shinto sought to return to a pure Japanese spirit, before it was “corrupted” by external influences, mainly Buddhism. The new order dismantled the combined temple-shrine complexes that had existed for centuries. Buddhists priests were no longer able to practice at Shinto shrines and Buddhist artefacts were removed from Shinto shrines.

This religious persecution of Buddhism, known as haibutsu kishaku (literally: “abolish Buddhism and destroy Shākyamuni”), saw the destruction and closure of many Buddhist institutions throughout Japan as well as the confiscation of their land, the forced defrocking of Buddhist monks and the destruction of Buddhist books and artefacts. In some instances, monks were attacked and killed.

Post WW2 The occupation government abolished state Shinto, establishing freedom of religion and a separation of religion and state which became an official part of the Japanese constitutional amendment in 1947.

Buddhist temples in post-war Japan experienced difficult times. There was much damage to be repaired and there was little funding for it.

In the 1950s, the situation slowly improved, especially for those temples that could harness tourism and other ways of procuring funding.

However, post-war land reforms and an increasingly mobile and urban population meant that temples lost both parishioners and land holdings.

In the 1960s, many temples were focused solely on providing services like funerals and burials. The term sōshiki bukkyō (funerary Buddhism), was coined to describe the ritualistic formalism of temple Buddhism in postwar Japan that was often divorced from people’s spiritual needs.

Over time the numbers of Buddhists in Japan started to grow again, with various temple and non-temple sects seeing more people developing an interest to once again compliment Japanese Shinto beliefs with Buddhist teachings.

Today over 46% of Japanese people consider themselves to be Buddhist, with the largest group (22%) being Jōdo Buddhists, a branch of the Pure Land Buddhism, established during the Kamakura period.

The Differences Between Temples and Shrines

As already mentioned Temples are Japanese Buddhist, and Shrines are Shinto. Both will typically comprise of various structures, often very similar in design but with a few distinct differences.

Temples will often include, but not always, a five story pagoda. Tall wooden structures where each level symbolises a fundamental element in Buddhism: earth, water, fire, wind, and space (or void).

Unlike in China, Japanese five story pagodas do not serve as the main building at the Temple, but as an accessory building in which holy relics may be enshrined. Nevertheless they are iconic and certainly a focal point of a Temple complex.

The five story pagoda is a Buddhist Temple building, however as in the past many Temples and Shrines were combined, so they are not entirely exclusive to Temples today.

A number of Shrines remain which used to be Shrine/Temple complexes, and thus contain a historic five story pagoda.

An example of a Shrine with a five story pagoda is Tōshō-gu in Nikkō, Tochigi prefecture, a Shrine dedicated to Tokugawa Ieyasu, the founder of the Tokugawa Shogunate.

So while the five story pagoda is a Japanese Buddhist structure, it can sometimes be found at Shinto Shrines and therefore is not the best way to physically differentiate between the two.

A more reliable indicator is the presence, or lack thereof, a Tori Gate.

The Tori Gate is an iconic structure exclusive to Shinto Shrines. They can be found at each entrance to a Shrine complex, and mark the boundary between the mundane world, and sacred spiritual world.

They also represent a path where Kami (Shinto gods) are welcomed and said to travel through.

When walking through/under a Tori Gate it is polite to walk not through the centre, but slightly to the side, reserving the space in the middle for the Kami.

Some Shrines will have many more smaller Tori Gates within the main complex, often provided by local families and businesses as a way to pay respect and support the Shrine.

While many Tori Gates are painted in vibrant vermillion, they are also often made of stone or bronze or even left unpainted, such as the gates around Meiji Jingu Shrine in Shibuya, Tokyo.

Praying At Temples & Shrines

As a tourist or even a foreign resident, you are welcome to visit and pray at both Temples and Shrines. For the most part, Japanese people are happy to share their cultural beliefs and spiritual places with you.

Many Temples and Shrines have become iconic tourist destinations for domestic and international travellers.

When you visit Temples and Shrines, be respectful. You are welcome there, but if you display a disrespectful attitude or misbehave not only will you cause friction, but you may also end up in trouble.

Donations & Offerings

When visiting a Temple or Shrine it is expected that you will pay a small offering/donation to support the maintenance of the place.

It is quite normal and both tourists and locals pay this.

When you pray at any Temple or Shrine there will be a donation box, place the donation in here before you pray. There is no set amount, how much you pay is up to you. I usually put a ¥100 coin which is about £0.50 or $0.70USD, however it is said that when at a Shrine, to include a ¥5 coin will bring you good luck.

In Japanese ¥5 is spoken as “go en” which sounds like 御縁 “go-en” roughly translating as “good connection” or “relationship”, which is said to establish a good connection with the deity.

There are some people however who disagree with this, believing that ¥5 and ¥50 coins are actually unlucky due to their central hole.

So whether or not you include a ¥5 coin is up to you, but be sure to donate something as Temples and Shrines rely on these donations to maintain the buildings and running costs.

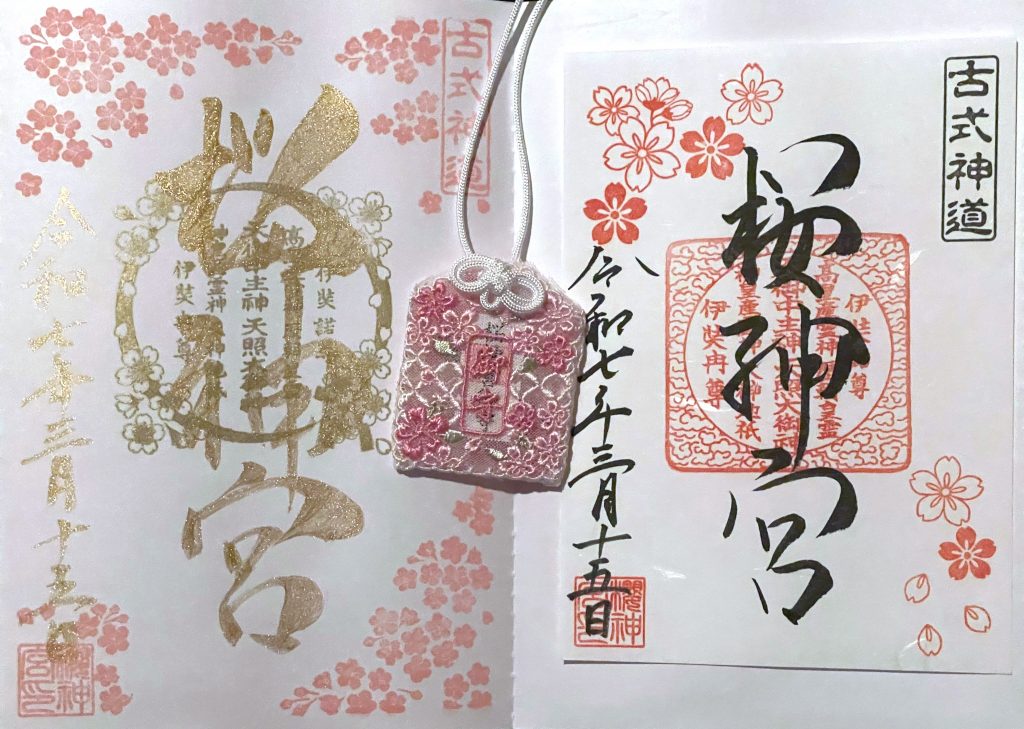

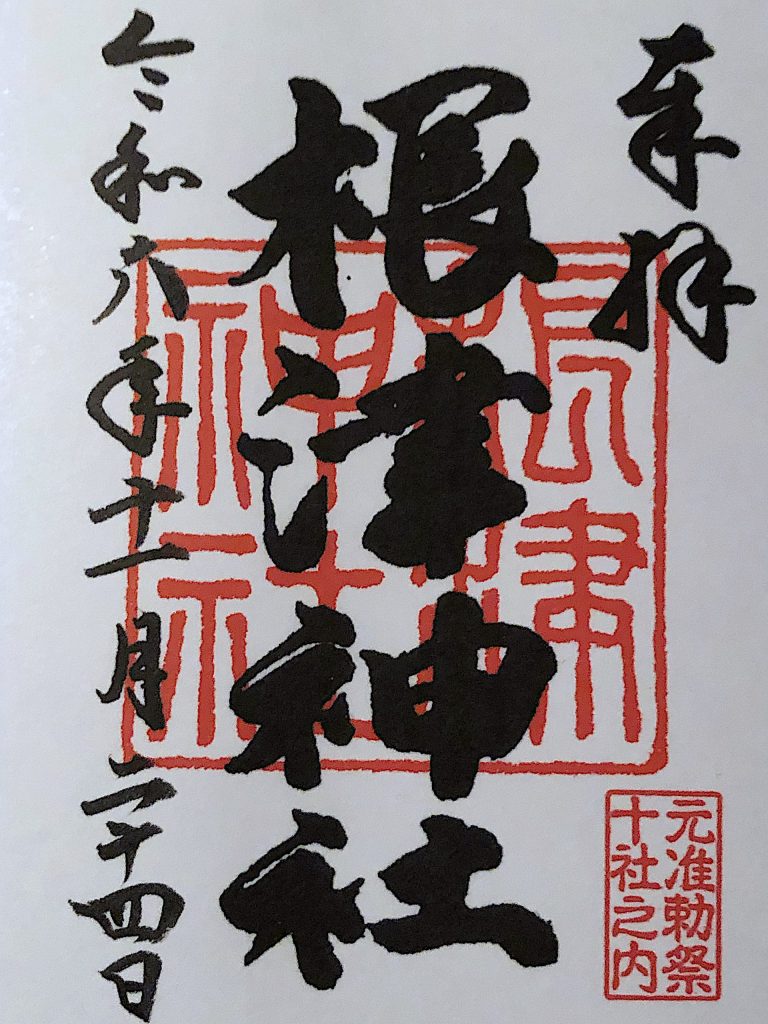

You can also purchase items such as pendants, “omamori” amulets and “goshuin” which are Japanese calligraphy and red ink stamps unique to each Temple and Shrine.

They can serve as a record of your visit, aiding in memory of the experience and providing a physical link to the Temple or Shrine, and the cost goes towards supporting it.

Many people like to keep their goshuin in a special book called goshuincho.

How To Pray

Both Temples and Shrines have particular ways to pray…

If there is a fountain it is customary to purify yourself by rinsing both hands using the ladle (if provided), and also cupping some water to the lips.

Refilling the ladle and tipping it upwards slightly allowing the water to trickle down the handle cleans it for the next person to use.

Temples

- Make your offering by placing the coins in the box provided

- Ring the bell, if one is present by the offering box

- Bow twice, bow deeply and respectfully

- Place your hands together with the right slightly lower than the left

- Pray silently, with your hands still together

- Bow once more

- Before leaving the Temple grounds, bow once more facing the main hall

Shrines

Shrines are very similar to temples with the inclusion of a clap…

- Make your offering by placing the coins in the box provided

- Ring the bell, if one is present by the offering box

- Bow twice, bow deeply and respectfully

- Clap your hands twice, holding them together on the second clap

- With your hands still together slide the right hand slightly lower than the left

- Pray silently, with your hands still together

- Bow once more

- After passing through the Tori Gate when leaving the grounds, bow once more facing the gate

While the general prayer format is standard, some Shrines might have their own specific customs or traditions.

If in doubt you can ask or simply follow the actions of others as a guide, although even Japanese people can get it wrong sometimes.

Temple & Shrine Etiquette

When visiting Temples and Shrines in Japan it is important to be respectful and non-disruptive at all times.

Keep your voice low in volume to preserve the quietness and atmosphere.

While most are fine with you taking pictures or short videos, do not take any of other people without permission.

Some sites may display signs prohibiting photography. If you see a sign stating no photography then please keep your cameras away, this means no videos too.

While you are welcome to take your time and enjoy the sense of peace and tranquility that these places often provide, do not sit around treating it as a hang-out space.

Do not cause damage!

Unfortunately there have been instances, although rare, of people carving their names into Tori Gates or adding graffiti to various statues and structures.

Thank you for reading!